Needle Stick Injury (NSI), according to the National Surveillance System for Healthcare Workers (NASH), is any percutaneous injury or skin penetration due to a needle or other sharp object, which has previously been in contact and exposed to blood, tissue, or body fluids. Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at a higher risk of occupational exposure to NSIs. Today, more than 20 different pathogens are known to be transmitted by NSIs, the majority are viral infections like the Hepatitis B virus (HBV), Hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Risk of infection varies from 30 percent for HBV, 3 percent for HCV and 0.3 percent for HIV. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that exposure to blood and body fluids by NSIs affects approximately three million healthcare workers annually although only 10 percent of these injuries are reported. In developing countries, which have the highest global prevalence of HIV, the prevalence of NSIs is also at the highest level.

Globally, an estimated 1 in 10 healthcare workers experience a sharp injury each year. According to WHO research, the estimated number of healthcare workers exposed to blood-borne viruses worldwide is 2.6 percent (16,000) for HCV, 5.9 percent (66,000) for HBV, and 0.5 percent for HIV. The impact of NSIs is not limited to possible infections only.

The prevalence or pattern of needle stick injury differs from one healthcare set up to another, from one society to another and from one country to another. Worldwide, there is extreme under-reporting of NSIs, which is 10 times lower than the actual rate in many instances.

Among the health care workers, nurses are at a greater risk of needle stick injury compared to others due to their frequent performance of injections and venipuncture and the provision of care to patients infected with hepatitis C and B and HIV. The heavy workloads, inadequate nurse-to-patient ratio, frequent shifts and excessive fatigue are among the top factors contributing to an increased prevalence of needle stick injuries among nurses, especially in developing countries.

Accidental NSIs are an occupational hazard for healthcare workers. Despite the implementation of preventive measures, NSIs continue to occur in healthcare settings. The cost incurred by an institute for managing occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens is a significant economic burden. This retrospective study aimed to estimate the occurrence of needle stick injuries among healthcare workers in a tertiary care hospital in Patna.

Need for the study:

The present study does a retrospective analysis of needle stick injuries aimed at determining the occurrence of needle stick injuries among healthcare workers in a tertiary care hospital in Patna (Bihar).

Objectives This study attemp

ted to determine the occurrence and quantum of needle stick injury among health care workers.

Review of Literature

A study conducted in Pune regarding the financial impact of needle stick injuries on a tertiary care hospital found that nurses were the most affected category of HCWs. For three years, hospitals spent Rs. 13,21,206, which included both direct and indirect costs, on managing NSIs (Dhayagude et al, 2022).

A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the frequency, causes and prevention of needle stick injuries in nurses of Kerman. The results show syringe needle heads and Angio catheters are the main causes of needle stick injuries. Hence there is need for providing safe medical equipment should also be emphasised (Balouchi et al, 2015).

A study was conducted to determine the risk factors of NSIs among healthcare workers in CMC Vellore (TN), between July 2006 and June 2007. This is a 2234-bed tertiary care hospital that serves as the teaching hospital for colleges of medicine and nursing. The Staff Student Health Service has maintained an NSI register since 1993. If a health worker sustains a needle stick injury, he/she is to induce bleeding from the wound, wash with soap and water and report to the Staff Student Health Services doctor immediately. The duty doctor completes a proforma, which has details of the source, health worker details, vaccination status, the details of the incident and whether necessary precautions were followed by the health care workers. The result shows that among the 296 healthcare workers those reporting NSIs were 84 (28.4%) nurses, 27 (9.1%) nursing interns, 45 (21.6%) cleaning staff, 64 (21.6%) doctors, 47 (15.9%) medical interns and 24 (8.1%) technicians. Among the staff who had NSIs, 147 (49.7%) had a work experience of less than 1 year (p < 0.001). The devices responsible for NSIs were mainly hollow bore needles (n = 230, 77.7%). In 73 (24.6%) of the NSIs, the patient source was unknown. Recapping of needles caused 25 (8.5%) and other improper disposal of the sharps resulted in 55 (18.6%) of the NSIs. Immediate post-exposure prophylaxis for HCWs who reported injuries was provided. The subsequent 6-month follow-up for human immunodeficiency virus showed zero seroconversion. The study concludes that improved education, prevention and reporting strategies require to be emphasised on appropriate disposal. Further, there is need for increased occupational safety for healthcare workers (Jayanth et al, 2009).

A study was conducted to assess the occurrence of NSIs among HCWs in New Delhi. The study group consisted of 428 HCWs in tertiary care hospitals and was carried out with the help of an anonymous, self-reporting questionnaire structured specifically to identify predictive factors associated with NSIs. The commonest clinical activity to cause NSI was blood withdrawal (55%) followed by suturing (20.3%) and vaccination (11.7%). The practice of recapping needles after use was still prevalent among HCWs (66.3%). Some HCWs also revealed that they bent the needles before discarding these (11.4%). It was alarming to note that only 40 percent of the HCWs knew about the availability of PEP services in the hospital, and 75 percent of exposed nursing students did not seek PEP. The study found a high occurrence of NSI in HCWs with a high rate of ignorance and apathy. These issues need to be addressed through appropriate education and strategies by the hospital infection control committee (Muralidhar et al, 2010).

In a cross-sectional study to assess the prevalence and response to needle stick injuries among healthcare workers in Delhi, the data was collected from 322 resident doctors, interns, nursing staff, nursing students, and technicians. Proportions and the chi-square test were used for statistical analysis. The results show a large percentage (79.5%) of HCWs having reported one or more NSIs in their career. The average number of NSIs ever was found to be 3.85 per HCW (range 0-20); 72 (22.4%) having reported received an NSI within the last month. Over a third of the injuries (34.0%) occurred during recapping. In response to their most recent NSI, 60.9 percent washed the site of injury with water and soap, while 38 (14.8%) did nothing. Only 20 (7.8%) of the HCWs took postexposure prophylaxis PEP against HIV/AIDS after their injury. The study concludes that NSI was found to be quite common. Avoidable practices like the recapping of needles were contributing to the injuries. Prevention of NSI is an integral part of prevention programmes in the workplace, and training of HCWs regarding safety practices indispensably needs to be an ongoing activity at a hospital (Polit & Beck, 2012).

Materials & Methods

This retrospective analysis was conducted among healthcare workers from 1 April 2023 to 31 March 2024 in the HIC office of a tertiary hospital in Patna (Bihar). All HCWs (Sample-116) who were exposed to needle stick injuries during the period reported the incidents to the HIC office of the hospital with prefilled needle stick injury Performa. The Hospital Infection Control office records detailed information about every needle stick injury in the hospital using a structured Performa which includes age, gender, designation, CR number, location of the injury, site of the injury, type of device causing the injury, the patient’s blood-borne infection status, vaccination status and so on. The registered forms are used for retrospective analysis.

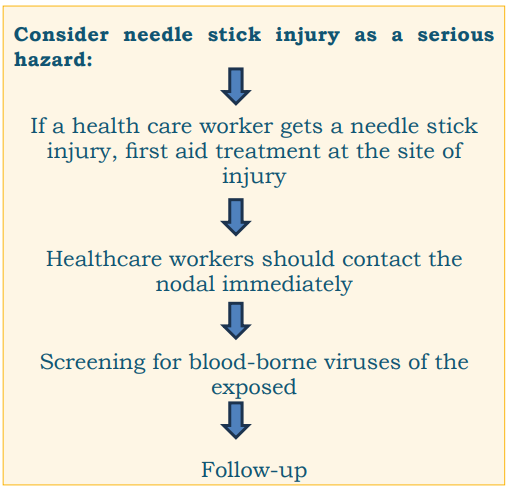

The procedure adopted and fellow-up is shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1: Reporting to follow-up of needle stick injury cases.

Data collected through registered forms are entered into spreadsheets for further analysis.

Results

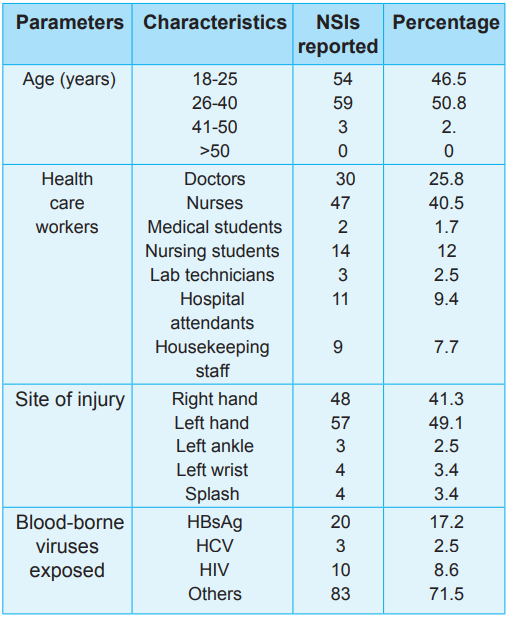

Out of 116 needle stick injuries reported, 59 cases were aged 26-40 years. Nurses were more exposed to needle stick injury compared to other cadres of health care workers. The site of needle injury was the right & left hand in reported cases. Out of 20 needle stick injuries exposed to bloodborne viruses, 15 needle stick injuries were given post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV & HBs Ag (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic parameters of needle stick injury among healthcare workers

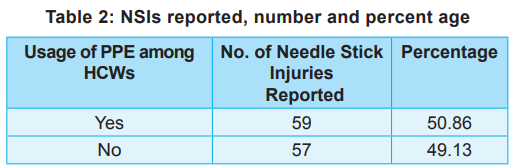

Usage of Personal Protective equipment (PPE)

The use of PPE in those healthcare workers who contract needle stick injuries was analysed (Table 2).

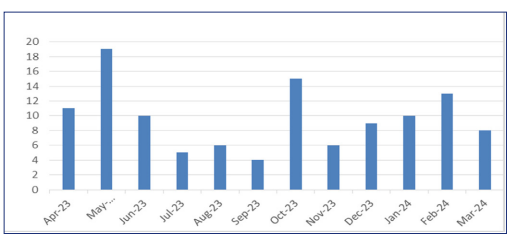

Needle stick injuries according to months

There were 116 cases of needle stick injuries reported from 1 April 2023 to 31 March 2024 (Fig 2). The greatest number of cases were reported in May 2023 (19 cases) and least were reported in July 2023 (5 cases).

Fig 2: Needle sick injuries reported, month-wise.

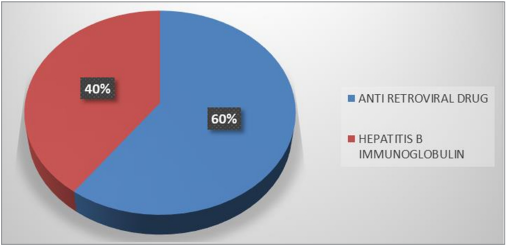

Post-exposure prophylaxis was given to the source-positive needle stick injury cases (Fig 3).

Discussion

According to the CDC, every year, more than 3 million HCWs are exposed to blood and body fluids via sharps and splash injuries in the United States. Needle stick injuries pose a greater risk to the HCWs as they are exposed to transmission of blood-borne viruses including HBs Ag, HCV and HIV. Occupational injuries with needles and sharps are commonly seen among HCWs, leading to higher morbidity. PPE is known to be an important line of defense against needle stick injuries.

The present study findings correlate with a study conducted at Mogadishu Somali Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan Training & Research Hospital over six years between 2017–2022 in a tertiary care hospital in Somalia, where most of the cases who contract needle stick injury were between the age group 26-40 years (around 141 cases). Nurses were at risk of needle stick injury, and around 122 cases were reported compared to other categories of HCWs (Sharma et al, 2010). In the study, the site of injury was the right & left hand. The number of cases reported were around 98 & 96, respectively. In this study, most of the cases were not exposed to any blood-borne viruses.

The effective strategies to prevent needle stick injuries are education, orientation & induction training, safe injection practices and effective communication. Both will raise HCWs’ awareness and knowledge regarding needle stick injury and its management. Safe injection practices and advanced technology would help HCWs prevent the incidence of needle stick injuries. Lastly, effective and efficient IPR along with adequate monitoring by clinical supervisors would prevent the underreported incidence of needle stick injuries among HCWs.

Ethical consideration:

The data was collected from the study sample after obtaining approval from HICC, AIIMS Patna.

Recommendations

Some recommendations for reducing the risk of NSIs include: Provide regular training on the safe use of sharp devices; Implement safety precautions and safe injection practices; Provide engineered safety devices; Develop a routine programme to deal with Needle stick injuries; Strengthen infection control policies; Ensure implementation of standard precautions.

Fig 3: Post-exposure prophylaxis for the exposed person.

Nursing Implications

The study has implications for nursing education, nursing practice, nursing administration and nursing research.

The collaboration of hospitals and educational institutions is essential to develop effective NSI prevention programmes.

There is a need for greater and continuing education on universal precautions or standard procedures in all categories of healthcare professionals.

Acknowledgement:

The author express thanks to the participating subjects for their contribution in the study.

Conclusion

Healthcare workers around the world continue to face major hazards from needle stick injuries. The incidence rates of NSIs are higher among nursing officers and housekeeping staff. The establishment of formal reporting mechanisms, immediate reporting of NSIs, and the establishment of comprehensive NSI prevention programmes, which include safe injection practices will help reduce the occurrence of NSIs and help in taking immediate remedial action in the form of prophylaxis and treatment. In-service education and continuing nursing education must be provided to nursing and allied staff to reduce the burden of needle stick injuries

1. Alsabaani A, Alqahtani NSS, Alqahtani SSS, Mahmood SE, Al-Lugbi M, Asin MAS, Salem SEE, et al. Incidence, knowledge, attitude and practice toward needle stick injury among healthcare workers in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. Front Public Health 2022 Feb 14; 10 (10:771190. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.771190. eCollection 2022

2. Dhayagude S, Tolapadi A, Mane A, Modak M. Financial impact of needle injury on a tertiary care teaching hospital: A retrospective study. Clinical Epidemiology & Global Health 2024; 29 (12):101726

3. Balouchi A, Shahdadi H, Ahmadidarrehsima S, Rafiemanesh H. The frequency, causes and prevention of needlestick injuries in nurses of Kerman: A cross-sectional study. J Clin of Diagn Res 2015; 9 (12): DC13-DC15

4. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 9th edn, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

5. Jayanth ST, Kirupakaran H, Brahmadathan KN, Gnanaraj L, Kang GG. Needle stick injuries in a tertiary care hospital; Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology 2009 Jan-Mar 27(1): 44-47

6. Muralidhar S, Singh PK, Jain RK, Malhotra M, Bala M. Needle stick injuries among health care workers in a tertiary care hospital of India. Indian Journal of Medical Research 2010 Mar; 131 (3): 405- 10

7. Sharma Rahul, Rasania SK, Verma Anita, Singh Saudan. Study of prevalence and response to needle stick injuries among health care workers in a tertiary care hospital in Delhi, India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine January 2010; 35(1): 74-77. DOI:10.4103/0970-0218.62565

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.