All over the world, the education of healthcare professionals has changed significantly in the past few decades due to the concern for the patient’s safety. “To err is human.” A landmark report released by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 1999 in the USA estimated that as many as 98,000 people die in any given year from medical errors that occur in hospitals. That’s more than the deaths from motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, or AIDS (Kohn et al, 2000). According to WHO, there is a one in a million chance of a person being harmed while travelling by plane. In comparison, there is a 1 in 300 chance of a patient being harmed during health care. Patient harm is the 14th leading cause of the global disease burden, comparable to tuberculosisand malaria (World Health Organization, 2019).

Nurses play a critical role in ensuring patient safety. Their proficiency in several clinical skills is linked to patient outcomes. According to Max Mayfield, preparation through education is less costly than learning through tragedy. A major challenge for nursing students is the application of their theoretical knowledge to the management of patients. Students sometimes complete their courses with theoretical knowledge but lack essential clinical skills. The curriculum must provide opportunities to develop critical thinking, clinical decision-making ability, and psychomotor skills. Gaining skills requires repeated practice of desired skills. The opportunity to engage in real-life problem-solving is limited. In addition, practice in real-life situations without systematic guidance is associated with risks and ethical issues. Moreover, real-life situations only sometimes provide enough practice opportunities as critical situations appear less frequently. These limitations make practice in real-life situations a somewhat inaccessible and sometimes sub-optimal learning space. Therefore, simulation-based learning (SBL) can be a useful approach that provides opportunities to practice clinical and decision-making skills without causing patient risk. It also provides an opportunity to practice rare emergencies (Issenberg et al, 2005).

In addition, it promotes retention of learning through experiential learning, which is defined by well-known maxims like: “I hear, and I forget, I see, and I remember, I do, and I understand.” (Confucius, 450 BC). “Tell me I forget, teach me I remember, involve me, I will learn.” (Benjamin Franklin, 1750). According to the 70- 20-10 model developed in the 1980s, 70 percent of our knowledge comes from experience and trying new things (Issenberg et al, 2005). Kolb’s Learning Styles and Experiential Learning Cycle says that effective learning is seen when a person progresses through a cycle of four stages: (1) Having a concrete experience (2) Observation of, and reflection on that experience, which leads to (3) the formation of abstract concepts (analysis) and generalisations (conclusions) which are then (4) used to test a hypothesis in future situations resulting in new experiences (Blackman et al, 2016). This type of learning is possible in SBL.

Need and significance of the study:

Many studies, including meta-analysis, showed that SBL was effective in various situations of learning (Abelson, 2017). An integrative review of medical and nursing literature was conducted by Ravert, who reported that 75 percent of the studies indicated positive effects of SBL on knowledge acquisition and/or skills training (Kim et al, 2015). JSBL sessions significantly enhance communication skills, help in seeing and managing even the rarest of cases, overcome the problem of uncooperative patients, increase the confidence of students in dealing with real patients, and provide immediate feedback during simulation (Ravert, 2002). Studies also show that SBL leads to increased knowledge, selfconfidence, and understanding, with some having reported implementation in clinical practice. Simulations are among the most effective ways to learn complex skills (Salgado et al, 2019; Chernikova et al, 2020).

SBL is currently getting more attention in nursing and is being recommended by the Indian Nursing Council for the BSc nursing curriculum. Establishing a high-fidelity lab requires a lot of money and is not possible in most institutions. Hence, it is beneficial to know the extent to which a moderate fidelity simulation will influence learning in nursing. Hence, this phenomenological study attempted to explore the experiences of nursing students who had undergone moderate-fidelity simulation-based learning in selected nursing colleges of Kerala.

Objectives

To explore nursing students’ experiences in moderate-fidelity simulation-based learning.

Review of Literature

A review of the literature reveals that SBL sessions significantly enhance communication skills, help in seeing and managing even the rarest of cases, overcome the problem of uncooperative patients, increase the confidence of students in dealing with real patients, and provide immediate feedback during simulation (Ravert, 2002). SBL leads to increased knowledge, self-confidence, and understanding. Simulations are among the most effective ways to learn complex skills (Salgado et al, 2019; Chernikova et al, 2020). The major themes identified in the review were “from uncertain expectations to the real experience of simulation-based learning (Skedsmo et al, 2023); anxiety/stress (Foronda et al, 2013); specific, clinical practice area, learner outcomes/ identified skill acquisition, elements of simulation design, simulation as pedagogy (Cantrell et al, 2017) the simulation-based training promoted selfconfidence, understanding from simulation-based training improved clinical skills and judgements in clinical practice. Simulation-based training emphasised the importance of communication and team collaboration (Hustad et al, 2019) knowledge and skills, attitude, self (learning, efficacy, determination, competency, confidence, utilisation, satisfaction, assessment); and Com(n)(competency, communication, and confidence) and P (perceptions and performance) (Rajaguru & Park, 2021) and the learning experience and professional growth through collaboration (Weismantel et al, 2024). Researchers couldn’t identify any Indian studies in nursing. Few studies conducted among MBBS students revealed that SBL gives hands-on practice, learning without clinical time constraints, and bridging theory to practice (Gorantla et al, 2019).

Methodology

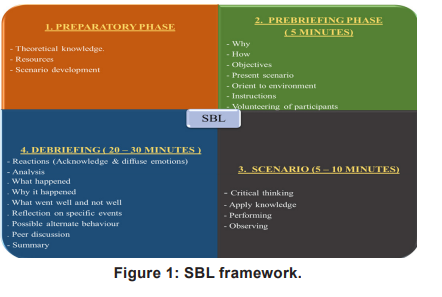

The objective of the study was to explore nursing students’ experiences in moderatefidelity simulation-based learning. A descriptive phenomenological design was used. The settings were two nursing colleges in Kerala (Baby Memorial College of Nursing, Kozhikode, and DM WIMS College of Nursing, Wayanadu), which were ready to train their teachers in SBL and to include SBL in their curriculum for student training. All teachers in the selected colleges were given training in conducting SBL. All faculty members in the selected institutions were given training in SBL by organising a workshop including lecture-cum-discussions, demonstration of facilitating SBL, training in preparation of scenarios, and hands-on training in conducting SBL sessions. The simulation sessions used for student training were of moderate fidelity. Teacher training was from August 2021 to March 2022. After training the teachers, SBL was made a part of student training in all nursing programmes and in all subjects. Students in all years of study in all programmes like MSc Nursing, Post Basic BSc Nursing and BSc Nursing received one-week SBL sessions in their concerned subject areas like Adult Health Nursing, Child Health Nursing, Obstetric Nursing, Community Health Nursing, Mental Health Nursing etc. Students were divided into groups of 10 students and scenarios were prepared according to their level of study. Data collection was done from January 2023 to October 2023. The framework used for SBL included prebriefing, scenario, and debriefing sessions (Fig 1). A total of 19 students from all nursing programmes were selected for the study by purposive sampling, and the sample size was determined by data saturation. An in-depth one-time interview was used for data collection. The duration of the interviews was about 30 to 45 minutes. All interviews were audio recorded.

Figure 1: SBL framework.

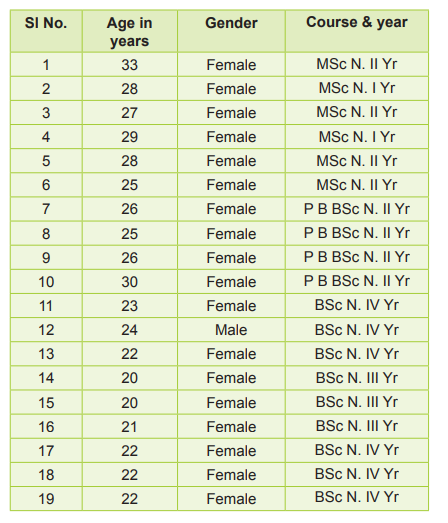

Table 1: Characteristics of participants

Results

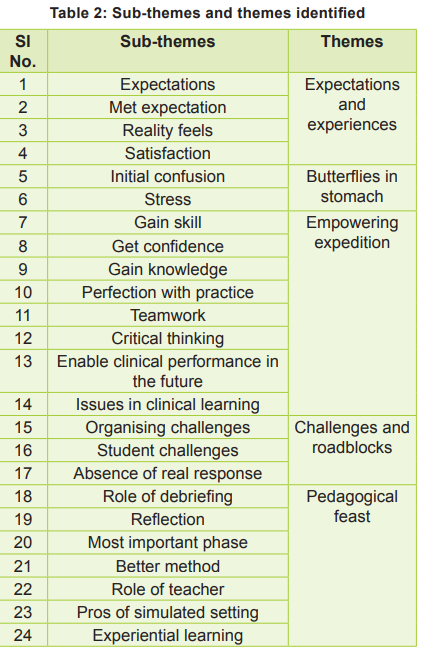

Data were collected from 19 students. Nine participants were from the BSc Nursing course, six from the MSc Nursing course, and four from the Post Basic BSc Nursing course (Table 1). The interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated into English by language experts. The data were analysed using Colaizzi’s seven-step model of phenomenological analysis. Each transcript was read and re-read to obtain a general impression of the whole content. Significant statements about the phenomenon under study were extracted from each transcript. The formulated meanings were sorted into sub-themes and themes. Rigour and trustworthiness were ensured by following Lincoln and Guba’s model. Credibility was ensured by prolonged engagement in the field by maintaining reflexivity. Member checking and expert review were also used at every step. An audit trail was maintained and submitted for review by an expert. Finally, validation of the findings was sought from the research participants. Analysis revealed 134 codes, 24 sub-themes, and five themes (Table 2). The themes are explained below.

Table 2: Sub-themes and themes identified

Expectations and Experiences

Before starting the actual SBL sessions, students had varying expectations about the SBL, ranging from a real-life situation or hospital in the lab to a mock drill in which they had to act. Students felt it very interesting as they expected they could practice what they had learned in theory classes, which would help improve their knowledge and skills. In the end, it was a very satisfying experience for the students and very useful for them as they could apply their theoretical knowledge as they expected. Once they were in the scenario, most felt it was very realistic and authentic, and they performed as if in a real clinical situation. A postgraduate student said, “I felt it as realistic. When the condition of a patient becomes bad, we act as if it is a real case”. However, two participants commented that it was only partially realistic. The factors that reduced realism were that they could not see the actual patient response as they had a simulated patient, and all the team members were their peers. An undergraduate student said, “I have not felt it as completely realistic. This is because all roles are played by peer groups. Seeing real patients is a different experience. The emotions of real patients and those who simulate as patients are quite different.”

Butterflies in Stomach

When students were given SBL sessions for the first time, they were having anxiety, stress, fear, and confusion. They feared performing wrong actions and also worried whether they would be able to perform well. They were confused and didn’t know what to do in the initial session, as SBL was new. Some students were having severe stress. Their anxiety and fear were reduced with repeated sessions, and later, they could act with confidence. Few participants reported that clear explanations about SBL and what is expected from students helped remove confusion and reduce their fear and anxiety. They felt confident and comfortable in the first session itself. Interestingly, two participants felt stress-free as they thought it was a simulated situation and there was no problem even if they committed mistakes as there was no patient harm. Another undergraduate student said, “I was comfortable because in simulation since it is not a real patient, we can utilize our knowledge to the maximum. We won’t do any harm to the patient as it is a scenario”.

Empowering Expedition

By undergoing immersive, interactive simulations, participants can develop essential skills and knowledge needed for clinical practice in a controlled and safe environment. This empowering approach enhances preparedness, builds confidence, and fosters a deeper understanding of the challenges in clinical areas. All participants reported that SBL improved their knowledge and skills and their confidence in handling similar situations during their clinical practice. SBL scenarios help students learn a procedure or task step by step by doing it repeatedly in a real situation. It also allows for identifying and correcting mistakes, clearing students’ doubts, and retaining knowledge better than classroom learning. To make it effective, students must come prepared with adequate knowledge and skills to apply them while acting in the situation.

They reported that in SBL, they were given real-life situations with simulated patients. So, they do not need to worry about the consequences of harming a patient. One undergraduate student said, “This won’t be possible in a hospital. In hospital, we have to take care of the patients, and we have to deal with the consequences.” This feeling gave them the confidence to act and learn so that they could perform better in real clinical situations.

The major benefit of SBL is that it allows learners to repeat tasks and scenarios multiple times in a real-like setting, reinforcing learning and preparing nurses to handle future emergencies in the hospital. This method is best suited for learning complex tasks and emergency procedures. When students face a situation for the first time in the hospital, they will have fear and confusion and won’t know what has to be done. They can overcome this by repeated practice in a real-life setting. According to one undergraduate student, “In traditional clinical teaching, we directly go to the patients with the knowledge we had from theory class. Naturally, we will feel some tension”.

By replicating complex emergencies in the clinical area, which necessitates students to think critically, make good judgments, prioritise tasks, apply knowledge, and solve problems, SBL also develops their critical thinking and decisionmaking skills. All these help students to go to clinical areas as empowered and confident nurses who can handle situations better, thus reducing chances of errors, confusion, and delays in patient care and, in turn, enhancing the quality of care given to patients. A postgraduate student said, “After the session, it was really helpful. I was able to perform each role in every situation without any fear and anxiety. After this session, I was able to do it in a much better way in the clinical setting. It was really helpful to approach the patient with that mindset and manage and give proper care to the patient”.

Another benefit of SBL is that students often may not get the opportunity to handle certain emergencies during their clinical posting. Even if there is a situation, experienced nurses will be taking the major role, and the students have to assist them or will be observers. Hence, they may not learn how to handle such a situation. In actual clinical areas, students will not get a second chance to correct mistakes by repetition. The best solution for handling these problems is to give simulations in laboratories. The only drawback of SBL is that students cannot see the actual patient response, especially when it is not a high-fidelity simulation.

The ability to work in teams and to effectively communicate with team members is important to a nurse. Giving opportunities to work in teams in simulated scenarios helps develop such skills among students. They recommended continuing SBL sessions in all courses.

Another undergraduate student reported that “Communication was improved in the acting phase and also in the de-briefing session while clearing doubts, but the major improvement was in the acting phase as it was teamwork.”

Challenges and Roadblocks

Though SBL is a better method for preparing student nurses for clinical exposure, it also imposes some challenges. The student and the teacher need a lot of preparation to use it effectively. Students expressed that SBL was effective because they came prepared to perform in the scenario. If they come without having theory knowledge and skill, there is no use in giving simulations. One undergraduate student reported that “lack of preparation and knowledge affected my confidence and it created stress and anxiety”.

The teacher must complete the theory and skill training sessions before SBL sessions. It is reported that anxiety and stress is a factor which may affect the performance of students.

The teacher can solve this by properly preparing the learners. Giving adequate explanations about the objectives, what SBL is, and what can be expected in the session will be helpful. This explanation is very important, especially in the first sessions, to reduce students’ anxiety, stress, and confusion so that they can practice appropriately and confidently in the scenario. Students also expressed that fidelity is very important for creating realism and stimulating students’ critical thinking and spontaneous acting. The setting should provide all necessary equipment and facilities as in the hospital setting. Good preparation of the simulated patient and good scenario planning will also help provide realism. One problem reported by the participants in using simulated patients is that the students cannot perform all procedures in a simulated patient and cannot see the actual responses to treatment. High-fidelity manikins are needed to manage this problem.

Students felt that though it is a good learning method for preparing students to manage clinical scenarios in a better way, time constraints are an issue. SBL is effective only if students have repeated sessions to identify and correct their mistakes, which takes a lot of time. It takes a lot of time to use SBL to teach every clinical situation.

One participant reported that students’ shyness can also hinder the effective utilization of this method. Shyness will make debriefing less effective. To be effective, the active participation of all students is important; otherwise, it is useless. One student observed that the teacher’s ability to supervise and identify the student’s strengths and weaknesses and bring them into debriefing is also important.

Pedagogical Feast

All participants reported that SBL as a pedagogical method is a better learning method than the traditional method as it allows experiential learning and involves students. Simulations replicate realworld situations, allowing learners to experience and interact with complex processes or environments in a controlled setting. It gives hands-on training in clinical skills and involves direct experience and practical application of knowledge and skills. Experiential learning provides the learners with an engaging and memorable learning experience. Participants identified many benefits of this learning method. This method arouses the interest of students as it’s a learner-centred method that encourages active participation, experimentation, and reflection by all students. This creates motivation for engaging in the learning scenario and thus promoting the learning process.

Many participants found that engaging in SBL stimulates their multiple senses, such as visual, auditory, tactile, etc. This provided a more comprehensive learning experience, clarified complex concepts, and resulted in better memory and retention of learning.

Participants felt that SBL is a powerful method to create a collaborative environment for group learning. This made learning easy and better and helped me learn by seeing what peers do. They felt that cooperation among learners is important for promoting learning. According to one undergraduate student, “SBL develops selfmotivation among each individual that makes to perform better than others. Performance among the peer group members can be compared, and each one can improve themselves”. Learners worked together to solve complex issues, which promoted teamwork and team communication. Every student will get the opportunity to manage complex situations, which may not be possible in actual clinical areas. Working in teams enabled learning from peers. One undergraduate student reported that “even now I remember the different roles performed by other classmates. This helped me a lot to improve my skills”.

It was found that in SBL both the acting in scenario and the debriefing phases are important for promoting learning. Some students felt that both the acting phase and debriefing were equally important, whereas some said debriefing was more important. Only one participant felt that the acting phase is more important as it helps in applying knowledge and doing a task step by step and promotes skill learning. Debriefing enables them to reflect on their decisions and performances and to understand their mistakes or omissions while acting in the scenario. This enabled them to improve their performance in the forthcoming sessions. Debriefing also enables the teacher to use positive reinforcement of correct behavior and correction of mistakes. Debriefing helped them to reflect on their actions and to identify their strengths and weaknesses. This also improved their critical thinking and analytic abilities.

Discussion

The themes identified in this study were expectations and experiences, Butterflies in the stomach, Empowering expedition, Challenges and roadblocks, and Pedagogical feast. A review of the literature identified six studies, including review articles and meta-synthesis. The studies reviewed covered SBL conducted at varying fidelity levels ranging from low, medium, and high fidelity. The findings of all studies are in line with the present study.

This study found that the students approached SBL with a lot of apprehensions, and in the end, it was a satisfying experience for them. Similarly, previous studies identified themes like “From uncertain expectations to the real experience of simulation-based learning” (Skedsmo Ket al,2023) and “anxiety/stress” (Foronda Cynthia, et al, 2013) and also reported that students were having expectations varying from anxiousness and embarrassment to expecting negative feedback and not anticipating any learning (Foronda et al, 2013).

In this study students reported that they gained knowledge, skills, critical thinking, communication ability, and confidence in going to clinical posting. It empowered them to manage real-life situations in the future and allowed them to practice repeatedly in real-life situations without harming patients. All the reviewed studies support these findings (Skedsmo et al, 2023; Weismantel et al, 2024).

Students identified completing theory sessions before SBL, adequate preparations by teacher and student for SBL, and time factor as the major challenges for using SBL for student training. One study reported that importance of prior preparation is important for effectively participating in SBL (Skedsmo et al, 2023).

In the present study, students identified SBL as a very effective pedagogical method with many advantages. It leads to learning and its retention by providing opportunities for experiential learning, arousing interest in learning, stimulating multiple senses, and providing a collaborative environment for teamwork. The debriefing session provides an opportunity for reflective learning and helps identify mistakes. It is a safe method for training as it does not involve any patient harm or ethical issues and allows repetition. Previous studies also report that SBL is a better pedagogical method for training nurses (Cantrell et al, 2017; Hustad et al, 2019).

Implications in Nursing

This study revealed that even medium-fidelity simulations can effectively prepare nursing students for clinical practice. By using SBL, educators can create participatory, effective, and lasting learning experiences for students, and can prepare them for the complexities of clinical practice. SBL can be easily incorporated in the curriculum of all nursing programmes and for onthe-job training for nurses, especially in managing emergencies and rare situations.

Ethical Considerations

This study does not involve any ethical issues. Yet, the study was conducted after getting ethical clearance from the IEC of Baby Memorial Hospital. Informed consent was taken from all participants before data collection.

Recommendations

1. An experimental study can be conducted to test the effect of SBL on competency, decision making and confidence of students in clinical practice.

2. A descriptive study can be conducted to identify the barriers and facilitators of SBL inclusion in the curriculum.

Conclusion

Exploration of students’ experiences in SBL revealed that moderate fidelity SBL improved their knowledge, skills, decision-making and communication abilities. They also felt that it prepared them for managing real-life situations in the clinical area. It allowed safe, repeated practice in real-life situations without fear of committing mistakes and harming patients. SBL must be incorporated into all nursing programmes’ curricula to develop well-equipped nurses to improve patient safety and quality patient care.

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25077248

2. 10 Global facts on patient safety. World Health Organization, 2019. Available from: https:// www.who. int/features/factfiles/patient_safety/en/

3. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach 2005; 27: 10–28

4. Blackman DA, Johnson SJ, Buick F, Faifua DE. The 70- 20-10 Rule for learning and development: An effective model for capability development. Conference paper, 2016. https://www.ccl.org/articles/leading-effectivelyarticles/70-20-10-rule/

5. Kolb’s Learning Styles and Experiential Learning Cycle, 2006 https://www.wgu.edu/blog/experiential-learningtheory

6. Abelsson A. Learning through simulation. Disaster and Emergency Medicine Journal 2017 Oct; 2 (3): 125-28. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320613941_ Learning_through_simulation

7. Kim J, Park JH, Shin S. Effectiveness of simulationbased nursing education depending on fidelity: Metaanalysis. Nurse Education Today 2015; 35(1): 176-82 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0672-7

8. Ravert P. An integrative review of computer-based simulation in the education process. Comput Inform Nurs Sep-Oct 2002; 20(5):203-08. https://pubmed.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/12352106/

9. Salgado AP, Philpot S, Schlieff J, Driscoll L, Mills. An Advanced Care Planning Simulation-based learning for nurses: Mixed methods pilot study. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 2019; 29: 1-8. https://www.nursingsimulation. org/article/

10. Chernikova O, Heitzmann N, Stadler M, Holzberge D, Seidel T, Fischer F. Simulation-based learning in higher education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research June 2020; 90 (4): https://www.researchgate. net/publication/320613941_Learning_through_ simulation

11. Skedsmo K, Bingen HM, Hofsø K, Steindal SA, Hagelin CL, Hilderson D, et al. Postgraduate nursing students’ experiences with simulation-based learning in palliative care education: A qualitative study - Nurse Education in Practice. BMC Palliat Care Journal 2023 Nov 1; 73:103832

12. Foronda C, Liu S, Bauman BE. Evaluation of simulation in undergraduate Nurse Education: An integrative review. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 2013; 9 (10): e409-e16. ISSN 1876-1399, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ecns.2012.11.003

13. Cantrell MA, Franklin A, Leighton K, Carlson A. The evidence in simulation-based learning experiences in Nursing education and practice: An umbrella review. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 2017; 13 (12): 634-67. ISSN 1876-1399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ecns.2017.08.004

14. Hustad J, Johannesen B, Fossum M, Hovland O. Nursing students’ transfer of learning outcomes from simulation-based training to clinical practice: A focusgroup study. BMC Nursing 2019 Nov; 18 (53). https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0376-5

15. Rajaguru V, Park J. Contemporary integrative review in simulation-based learning in nursing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021 Jan; 18(2): 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph18020726

16. Weismantel I, Zhang N, Burston A. Exploring intensive care nurses’ perception of simulation?based learning: A systematic review and meta?synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2024 Mar; 33(3): 1195-1208

17. Gorantla S, Bansal U, Singh JV, Dwivedi AD, Malhotra A, Kumar A. Introduction of an undergraduate interprofessional simulation-based skills training program in obstetrics and gynaecology in India. Adv Simul 2019; article no. 6, 6119. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41077-019-0096-7

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.