Ababy is a great blessing. Every year, an estimated 15 million babies are born preterm, and this number is rising. Pre-term birth complications are the leading cause of death among children under 5. Approximately 1 million neonatal deaths occurred in 2015. Three-quarters of these deaths could be prevented with current, cost-effective interventions. Across 184 countries, the rate of pre-term birth ranges from 5 percent to 18 percent of babies born.

Pre-term is defined as babies born alive before 37 weeks of pregnancy are completed. Induction or caesarean birth should not be planned before 39 completed weeks unless medically indicated. Most pre-term births happen spontaneously, but some are due to early induction of labour or caesarean birth, whether for medical or nonmedical reasons. Common causes of pre-term birth include multiple pregnancies, infections and chronic conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure; however, often no cause is identified. There could also be a genetic influence. A better understanding of the causes and mechanisms will advance the development of solutions to prevent pre-term birth. It is vital to investigate the knowledge of pre-term delivery among women (WHO, 2023).

Children who are born pre-term often have short-term morbidities such as respiratory difficulties, periventricular leukomalacia and infection. In the long term, many of these children suffer from neurological and developmental disabilities. Apart from the medical sequela of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), prematurity also has large economic consequences.

Approximately 10-12 percent of Indian neonates are born before 37 completed weeks. These infants are vulnerable to various physiological handicapped conditions with a high mortality rate due to their anatomical and functional immaturity. Pre-term birth is a major determinant of neonatal mortality and morbidity with long-term antithetical consequences for health. One to three children born pre-term have higher rates of cerebral palsy, sensory deficits, learning disabilities and respiratory illnesses compared with children born full term. Pre-term children are at greater risk of motor impairments which often persist into adolescence. About 10-20 percent of all pregnancies and 9 percent of neonates are at risk. According to international studies, 2.6-10 percent of all neonates are born with a birth weight of less than 1500 gm (Hidayat et al, 2015).

Earlier efforts have been primarily aimed at improving the survival and health of preterm infants, which have hardly reduced the incidence of pre-term birth. Increasingly, primary interventions endeavour to identify the knowledge on pre-term delivery among pregnant women (Goldenberg et al, 2008). The frequency of pre-term births is about 12-13 percent in the USA and 5-9 percent in many other developed countries. However, the rate of pre-term birth has increased predominantly due to increase in preterm births and pre-term delivery of artificially conceived multiple pregnancies.

Pre-term birth is a significant public health problem across the world because of associated neonatal mortality and short- and long-term morbidity and disability in later life. Pre-term is defined by the World Health Organisation as babies born alive before 37 completed weeks of gestation or fewer than 259 days of gestation since the first day of a woman’s last menstrual period (LMP). Normally, a pregnancy lasts about 40 weeks. Many of the pre-term babies who survive suffer from various disabilities like cerebral palsy, sensory deficits, learning disabilities and respiratory illnesses. The morbidity associated with pre-term birth often extends to later life, resulting in physical, psychological and economic stress to the individual and the family (CDC, 2024).

Pre-term birth is a global problem; more than 60 percent of pre-term births occur in Africa and South Asia. In the lower-income countries, on average, 12 percent of babies are born too early compared with 9 percent in higher-income countries. Within countries, poorer families are at higher risk. Survival of premature babies also depends on where they are born. Almost 9 out of every 10 pre-term babies survive in high-income countries due to enhanced basic care and awareness, in sharp contrast to about 1 out of 10 in low-income countries (CDC, 2024). Identification of risk factors in women with improved care before, between and during pregnancies; better access to contraceptives and increased empowerment/ education can decrease the pre-term birth rate.

Although the mortality rate for pre-term infants and the gestational age-specific mortality rate have dramatically improved over the last 3 to 4 decades, infants born pre-term remain vulnerable to many complications. Few studies have reported mortality and morbidity rates in gestational age-specific categories, which limits the information available for counselling of parents before a pre-term delivery and for making important decisions on the timing and the mode of pre-term delivery. The high rates of neurological injury in pre-term infants highlight the need for better neuroprotective strategies and post-natal interventions that support extrauterine neuro maturation and the neurodevelopment of infants born pre-term (Krymko et al, 2004).

Prevention of pre-term births includes improved quality of care before, between and during pregnancy to decrease the occurrence of pre-term birth with improved pre-term birth outcomes and care of premature babies to reduce deaths and disability among them.

Many women are unaware of how their health before conception may influence their risk of having an adverse outcome of pregnancy. Providing care to women and couples before and between pregnancies (inter-conception care) improves the chances of mothers and babies being healthy.

Objectives

The study sought to assess the knowledge of preterm delivery among pregnant women and to find out the association between knowledge of preterm delivery among pregnant women and selected variables.

Hypothesis

H1: There is a significant association between knowledge of pre-term delivery among pregnant women and selected variables.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at the antenatal outpatient department of the Institute of Maternal and Child Health (IMCH), Kozhikode, because IMCH, is functioning in the Kozhikode Medical College campus, and maintains the record of conducting the greatest number of deliveries per day in Asia. It is the largest referral and teaching hospital in Kerala that receives referral cases from seven northern districts of Kerala and handles many high-risk pregnancies whose outcomes include pre-term birth.

Sample size: 350; P=77%; q=23%; d=4.6 4pq/d2=335

The sample consisted of 350 pregnant women.

Study taken for calculation: A study conducted to assess the knowledge of the post-natal mothers regarding the problems of premature babies admitted to the NICU in selected hospital in Assam (Sherf et al, 2017). Consecutive sampling technique was used.

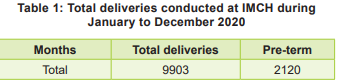

A total of 9903 deliveries (gestational age <37 weeks) were conducted at Institute of Maternal and Child Health during the period January to December 2020; of these 2120 were pre-term table 1).

Ethical approval:

Ethical clearance and written permissions were obtained. Before obtaining their consent, participants were well informed about the study; they were assured that the data would be kept confidential being for research purposes only.

Pilot study:

Earlier, after getting approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee of Government College of Nursing, Kozhikode, the pilot study was conducted from 5 to 11 February 2022. The data collected were amenable to statistical analysis, and the study was found feasible.

Data Collection Process

The study was conducted in the outpatient department of IMCH, Kozhikode. The sample was selected as per inclusion criteria. The purpose of study was explained to the participants, and informed consent obtained. Confidentiality was maintained.

After reviewing the record, the participants were comfortably seated in a room, and socio-personal data was collected through Tool I, Section A. Using the tool, Section B clinical data were recorded. Knowledge regarding pre-term delivery among pregnant women was collected using a semi-structured interview schedule, Tool I, Section C. About 30-35 minutes were taken for each participant for data collection. Data was collected from 350 participants from 28.02.2022 to 02.04.2022 with an average of 4 participants per day.

As participants were cooperative, no difficulties were faced during data collection. After data collection, participants’ doubts were cleared, and an information booklet on pre-term delivery was distributed to study participants. The data were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results

Socio-personal Variables

Out of 350 pregnant women, 40.9 percent of pregnant women belonged to the age group 24-29 years, and only 10.3 percent participants belonged to the age group of ≥36 years. As for education, 27.4 percent had secondary education qualification, and only 4.3 percent of them had either professional or technical education. Among 350 pregnant women, 61.1 percent were primigravidae and 39.9 percent multigravida. Only 6 percent of pregnant women had a history of pre-term delivery, 10.9 percent had a history of abortion, and 2.3 percent had a history of intrauterine death.

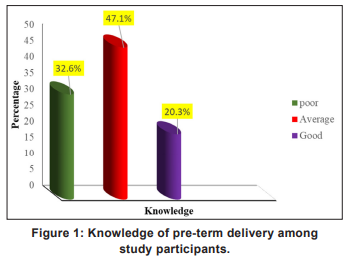

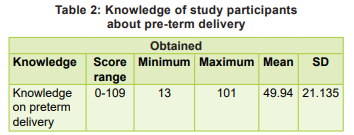

Regarding the awareness of pre-term delivery among pregnant women, 9.1 percent were already aware of pre-term delivery, and 6 percent received this information through mass media. The knowledge about pre-term delivery among participants is shown in Fig 1, and Table 2.

Association between knowledge on pre-term delivery among pregnant women and selected variables: A statistically significant association was found between knowledge regarding pre-term delivery among pregnant women and selected variables like age, education, occupation, occupation of husband, and history of pre-term delivery at a 0.05 level of significance.

Discussion

Our study revealed that 32.6 percent of pregnant women had poor knowledge regarding pre-term delivery, 47.1 percent had average knowledge, and 20.3 percent had good knowledge regarding pre-term delivery. These findings are consistent with those of the study on parental knowledge of prematurity and related issues in Singapore in 2009. Result was a pass in the entire and premature knowledge test scores were achieved in 69 percent and 62 percent out of 81 respondents. The study concluded that the majority achieved a pass-all true score; general knowledge among the childbearing group was deemed inadequate by the median score (Lalhmingthang et al, 2018).

Our findings are also in tune with those of the study on prematurity-related knowledge among 196 mothers and fathers of pre-term infants conducted during May-July 2017 in Portugal. The results showed that the parents had a median prevalence of pre-term and very pre-term delivery in Portugal of 15 percent and 8 percent, respectively.

The present study findings are supported by the one on knowledge of the 30 post-natal mothers regarding the problems of premature babies admitted at NICU in a selected hospital in Assam in 2018. Majority of post-natal mothers (n=23, 77%), had average knowledge and 7 (23%) had good knowledge. The study concluded that most of the post-natal mothers of premature admitted babies had an average knowledge regarding the problems of premature babies.

Our findings are in agreement with another study on knowledge and practice regarding care of pre-term babies among mothers at NICU in a selected Hospital in Andhra Pradesh. The study showed that majority of the mothers (n=15, 50%) had moderately adequate knowledge, 3 (10%) had adequate knowledge, 12 (40%) had inadequate knowledge and majority of the mothers 19 (63.3%) had fair practice, 7 (23.4%) had good practice, and 4 (13.3%) had poor practice.

There is a significant association between the knowledge of mothers regarding care of pre-term babies with their educational status; there was no significant association between the knowledge of mothers of pre-term babies and selected dependent variables. There is no significant association between the practice of the mothers of pre-term babies and selected dependent variables (Morfaw et al, 2021). However, our results do not concur with those of Aragao et al (2004) on knowledge of mothers of pre-term babies among mothers at the NICU in a selected hospital. This descriptive study in Rwanda showed that the mean score of mothers’ awareness about pre-term infant care was 59.3 percent.

The present study found a significant association between knowledge regarding pre-term delivery among pregnant women and selected variables like history of pre-term delivery at a 0.05 level of significance. This is concordant with the study on recurrence of pre-term delivery in women with such family history. The risk for pre-term delivery of the F2 parturient was 34 percent or greater if their mother (F1) at any of her births had delivered pre-term, controlling for parity, maternal age at delivery, and preeclampsia (adjusted odds ratio: 1.34, 95% confidence interval: -1.01 to 1.77; p=0.042).

The findings of present study revealed that a statistically significant association between knowledge and education (0.000, c2 value 35.43); these findings are supported by the findings of the study on knowledge and practice regarding care of pre-term babies among mothers at NICU in selected Hospital of Andhra Pradesh to assess the level of knowledge and practice regarding care of pre-term babies among mothers. A study showed a significant association between the knowledge of mothers regarding care of pre-term babies with their educational status.

The findings of our study (p=0.006, c2 =14.422) for the association between knowledge on pre-term delivery among pregnant women and selected variables were less than 0.05, which is concordant with the findings of the study on maternal unemployment, an indicator of spontaneous preterm delivery risk. Weekly duration of work (<40 versus ≥40 h) had no significant effect on the occurrence of spontaneous pre-term. Unemployed women presented a significant increase in the risk of pre-term delivery.

Limitations

The sampling technique being consecutive, generalisation of findings is limited.

Recommendations

A similar study can be replicated in another setting, or with a larger sample.

Conclusion

Our study findings revealed that 32.6 percent pregnant women had poor knowledge, whereas 47.1 percent had average knowledge, and only 20.3 percent had good knowledge on pre-term delivery. There was a significant association between knowledge regarding pre-term delivery among pregnant women and selected variables like age, education, occupation, occupation of husband, and history of pre-term delivery at a 0.05 level of significance.

1. Hidayat ZZ, Ajiz EA, Krisnadi SR. Risk factors associated with preterm birth at Sadikin General Hospital in 2015. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2016; 6(13):798- 806

2. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008 Jan 5; 371(9606): 75-84. doi: 10.1016/S01406736(08)60074-4. PMID: 18177778; PMCID: PMC7134569

3. CDC. Preterm Birth for Everyone. 2024. https://www.cdc. gov/maternal-infant-health/preterm-birth/index.html

4. Krymko H, Bashiri A, Smolin A, Sheiner E, Bar-David J, Shoham-Vardi I, et al. Risk factors for recurrent preterm delivery. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology 2004 Apr 15; 113(2): 160-63

5. Ratzon R, Sheiner E, Shoham-Vardi I. The role of prenatal care in recurrent preterm birth. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology 2011 Jan 1; 154(1): 40-44

6. Hu CY, Li FL, Jiang W, Hua XG, Zhang XJ, Cui S, et al. Prepregnancy health status and risk of preterm birth: A large, Chinese, rural, population-based study. Medical Science Monitor. International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research 2018; 24: 4718

7. Eliyahu S, Weiner E, Nachum Z, Shalev E. Epidemiologic risk factors for preterm delivery. Israel Medical Association Journal (IMAJ) 2002 Dec 1; 4(12): 1115-17

8. Fishman SG, Chasen ST, Maheshwari B. Risk factors for preterm delivery with placenta previa. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 2012 Jan 1; 40(1): 39-42

9. Soholm JC, Vestgaard M, Ásbjornsdóttir B, Do NC, Pedersen BW, Storgaard L, et al. Potentially modifiable risk factors of preterm delivery in women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2021 Sep; 64(9): 1939-48

10. Kim YJ, Lee BE, Park HS, Kang JG, Kim JO, et al. Risk factors for preterm birth in Korea. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation 2005; 60(4): 206-12

11. Temu TB, Masenga G, Obure J, Mosha D, Mahande MJ. Maternal and obstetric risk factors associated with preterm delivery at a referral hospital in northeastern Tanzania. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction 2016 Sep 1; 5(5): 365-70

12. Lam CM, Wong SF. Risk factors for preterm delivery in women with placenta praevia and antepartum haemorrhage: retrospective study. Hong Kong Medical Journal 2002 Jun 1; 8(3): 163-66

13. Murad M, Arbab M, Khan MB, Abdullah S, Ali M, Tareen et al. Study of factors affecting and causing preterm birth. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2017; 5(2): 406-09

14. Cobo T, Kacerovsky M, Jacobsson B. Risk factors for spontaneous preterm delivery. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics 2020 Jul; 150(1): 17-23

15. Tellapragada C, Eshwara VK, Bhat P, Acharya S, Kamath A, Bhat S, et al. Risk factors for preterm birth and low birth weight among pregnant Indian women: A hospital-based prospective study. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2016 May; 49(3): 165-175

16. Wen SW, Goldenberg RL, Cutter GR, Hoffman HJ, Cliver SP. Intrauterine growth retardation and preterm delivery: Prenatal risk factors in an indigent population. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1990 Jan 1; 162(1): 213-18

17. Ward RM, Beachy JC. Neonatal complications following preterm birth. BJOG: International Journal of Obstetrics &Gynaecology 2003 Apr; 110: 8-16

18. Ling ZJ, Lian WB, Ho SK, Yeo CL. Parental knowledge of prematurity and related issues. Singapore Medical Journal 2009 Mar 1; 50(3): 270-77

19. Matos J, Amorim M, Silva S, Nogueira C, Alves E. Prematurity-related knowledge among mothers and fathers of very preterm infants. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2020 Aug; 29(15-16): 2886-96

20. Lalhmingthang R, Nongmeikapam M, Devi Das B. Knowledge of the postnatal mothers regarding the problems of premature babies admitted to the NICU in a selected hospital in Assam. Indian Journal of Applied Research June 2018: 8(6). PRINT ISSN No. 2249-555x

21. Morfaw F, Gao A, Moore G, Bacchini F, Santaguida P, Mukerji A, et al. Experiences, knowledge, and preferences of Canadian parents regarding preterm mode of birth. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 2021 Jul 1; 43(7): 839-49

22. Dropi?ska N, Chmaj-Wierzchowska K, Wojciechowska M, Wilczak M. What is the state of knowledge on preterm birth? Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology 2020 Aug 15; 47(4): 505-10

23. Aragao VM, Silva AA, Aragão LF, Barbieri MA, Bettiol H, Coimbra LC, et al. Risk factors for preterm births in São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2004; 20: 57-63

24. Sherf Y, Sheiner E, Vardi IS, Sergienko R, Klein J, Bilenko N. Recurrence of preterm delivery in women with a family history of preterm delivery. American Journal of Perinatology 2017 Mar; 34(04): 397-402

25. Buchmayer SM, Sparén P, Cnattingius S. Previous pregnancy loss: Risks related to severity of preterm delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004 Oct 1; 191(4): 1225-31

26. Rodrigues T, Barros H. Maternal unemployment: An indicator of spontaneous preterm delivery risk. European Journal of Epidemiology 2008 Oct; 23(10): 689-93

27. Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Zeitlin J, Lelong N, Papiernik E, Di Renzo GC, Bréart G. Employment, working conditions, and preterm birth: Results from the Europop case-control survey. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2004 May 1; 58(5): 395-401

28. Harini B, Brundha MP, Preejitha VB. Knowledge, awareness and attitude about preterm birth and its causes among females of reproductive age group Bioscience Biotechnology Research Communications 2020 August; 13(7): 131-36

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.