Stress among school-age children has become a critical public health issue, exacerbated by the shift to online learning during the Covid19 pandemic. The loss of traditional classroom structures led to increased psychological distress. In India, this was amplified by technological disparities and limited support systems, resulting in significant academic and social stressors for children. Art therapy is a recognised, nonpharmacological intervention that uses creative expression to help children manage stress and enhance coping mechanisms. However, evidence of its effectiveness in community-based settings, specifically for pandemic-related stress in Indian children, remains limited. This study aimed to address this gap by systematically evaluating a structured art therapy programme's effectiveness in reducing perceived stress among school-age children attending online classes in an urban community of Bengaluru.

Need of the Study

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a global educational disruption, with India's extensive school closures impacting over 320 million students. The necessary shift to online learning created unprecedented psychological challenges for children, including heightened academic anxiety, social isolation, and the erosion of routines.

Chronic childhood stress can adversely affect neurological development and emotional regulation, making early intervention crucial. Art therapy is an ideal community-based intervention: it is developmentally appropriate for non-verbal expression, cost-effective, and accessible. Neurobiological research indicates it promotes neural integration and regulates stress hormones like cortisol.

Despite its advantages, systematic evidence on art therapy's effectiveness for pandemic-related stress in Indian children is limited. This study was designed to provide empirical evidence to support the integration of art-based interventions as a viable public health strategy for future crises.

Review of Literature

Art therapy has demonstrated significant efficacy in managing stress and anxiety across diverse pediatric populations. Madden et al (2010) conducted a landmark study with paediatric brain tumor patients, revealing that structured creative art therapy sessions significantly improved quality of life scores and reduced observable anxiety levels during outpatient chemotherapy treatments. The intervention's success was largely attributed to its unique ability to provide a constructive emotional outlet and instil a sense of control and autonomy during stressful medical procedures.

Recent advancements in neuroimaging research have begun to provide concrete evidence for the underlying neurobiological mechanisms of art therapy. King et al (2019) utilised fMRI technology to demonstrate that participation in art therapy sessions produced measurable changes in brain network organisation and functional connectivity, particularly in regions robustly associated with emotional regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex and the default mode network.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses consistently support the effectiveness of art therapy in school-age populations. Moula (2020) conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of 15 school-based art therapy programmes for children aged 5-12 years, reporting statistically significant improvements in anxiety reduction and overall quality of life measures. In a similar vein, Abbing et al (2018) analysed 26 studies involving art therapy for anxiety management, concluding that structured, short-term interventions consistently produced clinically significant anxiety reduction across various age groups.

Pandemic-specific research further underscores art therapy's particular relevance during crisis periods. Reddy & Banerjee (2021) demonstrated significant stress reduction following a series of brief, guided art therapy interventions conducted online with Indian children during the Covid-19 lockdowns. Complementing these findings, Kaur et al (2022) reported positive outcomes using mandala-based art therapy with children in Punjab, noting improvements in mood and self-reported anxiety levels. These studies collectively provide compelling evidence for art therapy's cultural appropriateness and practical applicability within diverse Indian contexts.

Objectives

This study was undertaken with following objectives.

1. To assess the baseline stress levels among school-age children attending online classes in a selected community area of Bengaluru.

2. To evaluate the effectiveness of a structured art therapy intervention in reducing stress levels among the study participants.

3. To determine associations between preintervention stress levels and selected sociodemographic variables.

Methodology

Research design

A quantitative pre-experimental design utilising a one-group pre-test post-test approach was employed to evaluate the intervention's effectiveness. Setting

The study was conducted in a selected residential community area of Bengaluru, (Karnataka). Data collection was conducted from 13 May 2022 to 30 June 2022.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval. Informed consent and child assent were obtained, and all procedures adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study population comprised school-age children (6-12 years) attending online classes in the selected community area. A convenience sampling method was used to recruit 50 participants who met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population and sampling

Children aged 6-12 years, regularly attending online classes (minimum 5 days per week), having parental consent, able to hold and manipulate basic art materials, and residing within the selected community area were included.

Children with pre-existing diagnosed psychological disorders/ severe cognitive impairments affecting comprehension of instructions, having physical disabilities preventing manipulation of art materials or currently participating in other structured stress management interventions were excluded.

Variables

Independent variable: The intervention delivered seven consecutive days of 30-40 minutes art therapy sessions using drawing and colouring to provide a non-judgmental outlet for emotional expression and stress processing.

Dependent variable: Stress levels as measured by the adapted stress rating scale.

Data Collection Tools

Section A: A socio-demographic questionnaire collected data on age, gender, family type, academic class, family income, daily online class duration, and the primary device used for classes.

Section B: A stress assessment tool was adapted from the Modified Perceived Stress Scale. It integrated visual elements from the Wong Baker Faces Scale to create a 10-item, 5-point Likert scale (scores 0-40) for children. Stress was categorised as mild (0-13), moderate (14-26), or high (27-40).

Validity and Reliability: Content validity was established through a rigorous review by an expert panel (5 experts in paediatric nursing and psychology). The tool demonstrated exceptionally high internal consistency for this sample, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.974.

Data Collection Procedure

Pre-test stress assessment was conducted using the validated tool in a quiet, comfortable setting. The art therapy intervention was implemented daily for seven consecutive days; each session lasted 30-40 minutes and included a mix of free drawing, guided imagery drawing, and structured colouring activities.

Children were provided with age-appropriate art materials and consistently encouraged to express themselves creatively without fear of judgement. Post-test assessment was conducted on 7 day immediately following the final intervention session using the same scale.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics summarised demographic and stress data. A paired t-test compared pre-/ post-intervention scores, and a chi-square test examined associations with demographics. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

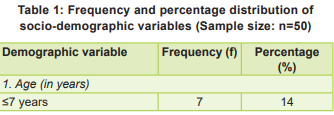

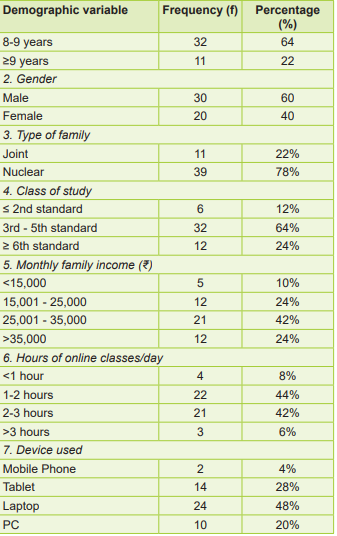

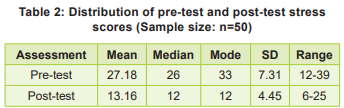

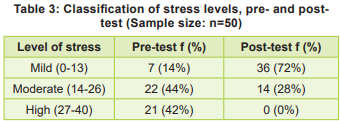

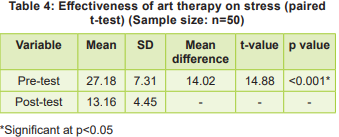

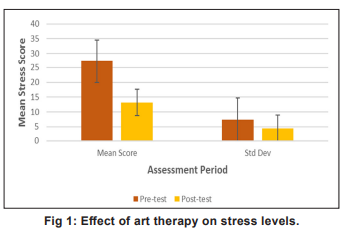

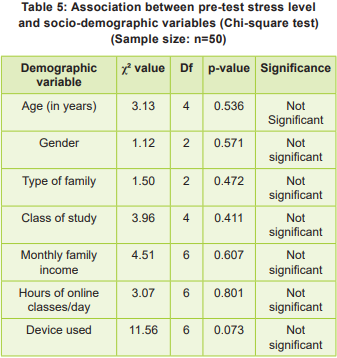

The frequency and percentage distribution of socio-demographic variables, distribution of pre- and post-test stress scores, classification of stress levels, effectiveness of art therapy on stress, effect of art therapy on stress levels, and association between pre-test stress level and socio-demographic variables are presented in Tables 1-5 and Fig 1.

Discussion

The study revealed a significant stress reduction following a seven-day art therapy intervention. The pre-test means stress score of 27.18 (SD±7.31), indicating moderate-to-high stress, decreased substantially to 13.16 (SD±4.45) post-intervention. This represents a clinically significant shift to the mild stress category for most participants, with a mean difference of 14.02 points. The 51.6 percent reduction demonstrates substantial effectiveness, a finding highly statistically significant (p<0.001) and aligned with international research.

The intervention's effectiveness is attributed to key mechanisms. Art therapy provides a safe, non-verbal medium for emotional expression, allowing children to externalise anxiety-provoking feelings, a process theorised to reduce internal psychological tension and promote emotional regulation. Additionally, engaging in the creative process activates neural reward pathways, promoting a state of relaxation and focused calm, or 'flow'.

A noteworthy finding was the absence of significant associations between demographic variables and baseline stress, suggesting that online learning stressors affected children universally across socioeconomic backgrounds. This contrasts with pre-pandemic research, highlighting the unique, pervasive nature of the Covid-19 crisis. The substantial results from a brief seven-day intervention support art therapy's efficiency as a crisis intervention tool. These findings are strengthened by consistency with recent Indian studies, providing strong evidence for the intervention's cultural appropriateness and effectiveness.

Study limitation:

A study limitation is the preexperimental design without a control group; future research employing a randomised controlled trial (RCT) would strengthen conclusions.

Recommendations

Policy integration: Develop guidelines to incorporate art therapy into school health curricula and emergency response protocols.

Professional training: Integrate art therapy modules into nursing education and offer workshops for healthcare workers and educators.

Community implementation: Establish sustainable art therapy programmes via local health centres or NGOs for stressed children.

Research advancement: Conduct rigorous RCTs with larger samples and longer follow-ups to confirm long-term efficacy and optimal dosage.

Comparative studies: Benchmark art therapy against other interventions (e.g., yoga, mindfulness) to guide resource allocation.

Nursing Implications

Practice: Community health nurses should integrate basic art therapy into pediatric care, school health programmes, and family counselling as an evidence-based tool for stress reduction.

Education: Nursing curricula must incorporate fundamental art therapy principles to equip future nurses with the skills to apply these lowrisk interventions in diverse settings.

Research: Nurse researchers should lead longitudinal studies to examine art therapy's longterm effects, optimal dosage, and mechanisms of action in specific pediatric groups.

Administration: Nursing leaders must advocate for policies that integrate creative therapies into public health systems, ensuring dedicated resources, space, and staff training.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a seven-day art therapy programme significantly reduced stress in school-age children during online learning. Pre-test scores dropped from a high-moderate level (27.18) to a mild level (13.16), a statistically significant mean difference of 14.02 points (p<0.001). This effectiveness across demographics confirms broad applicability.

The findings provide compelling evidence for art therapy as a practical, non-pharmacological intervention. Its cost-effectiveness and minimal resource requirements support its integration into school health and community programmes to safeguard children's psychological wellbeing during current and future public health challenges.

1. Madden JR, Mowry Patricia, Foreman NK. Creative arts therapy improves quality of life for pediatric brain tumor patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/ Oncology Nursing 2010 Apr; 27 (3); https://doi/10.1177/1043454209355452

2. Singh R. Online classes leading to stress, eye problems in children, say parents. Hindustan Times 2020; 20 July (https://www.hindustantimes.com/chandigarh/onlineclasses-leading-to-stress-eye-problems-in-children-sayparents/story-y4a8cnLKqHN8oCqozZ0psN.html)

3. Harjule P, Rahman A, Agarwal B. A cross-sectional study of anxiety, stress, perception and mental health towards online learning of school children in India during COVID19. J Interdiscip Math 2021; 24(2): 411-24

4. Chaturvedi K, Vishwakarma DK, Singh N. COVID-19 and its impact on education, social life and mental health of students: A survey. Child Youth Serv Rev 2021; 121: 105866

5. Raj U. Indian education system in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. SSRN Electron J 2020 (https:// papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3758853)

6. Kabir H, Hasan MK, Mitra DK. E-learning readiness and perceived stress among university students of Bangladesh during COVID-19: A countrywide crosssectional study. Ann Med 2021; 53(1): 2305-14

7. Hasan N, Bao Y. Impact of "e-Learning crack-up" perception on psychological distress among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Youth Serv Rev 2020; 118: 105355

8. Bosgraaf L, Spreen M, Pattiselanno K, van Hooren S. Art therapy for psychosocial problems in children and adolescents: A systematic narrative review. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 584685

9. Malchiodi CA. Trauma and Expressive Arts Therapy: Brain, Body, and Imagination in the Healing Process. New York: Guilford Publications; 2020

10. Slayton SC, D’Archer J, Kaplan F. Outcome studies on the efficacy of art therapy: A review of findings. Art Therapy 2010; 27(3): 108-18

11. Abbott KA, Shanahan MJ, Neufeld RWJ. Artistic tasks outperform non-artistic tasks for stress reduction. Art Therapy 2013; 30(2): 71-78

12. UNESCO. COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. Paris: UNESCO; 2020

13. Thompson RA. Stress and child development. Future Child 2014; 24(1): 41-59

14. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012; 129(1): e232-46

15. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the developing brain. Harvard University, 2014

16. Moula Z. A systematic review of the effectiveness of art therapy delivered in school-based settings to children aged 5-12 years. Int J Art Ther 2020; 25(2): 88-99

17. King JL, Kaimal G, Konopka L, Belkofer C, Strang CE. Functional brain connectivity and effectiveness of art therapy: A pilot study. Art Therapy 2019; 36(4): 201-09

18. Abbing A, Ponstein A, van Hooren S, de Sonneville L, Swaab H, Baars E. The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: A systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2018; 13(12): e0208716

19. Reddy KJ, Banerjee S. Impact of art therapy on perceived stress and mood in school-going children during COVID19 lockdown in India: A pilot study. Indian J Psychol Med 2021; 43(6): 543-47

20. Kaur R, Singh A, Sharma O. Evaluating efficacy of mandala art therapy in reducing anxiety among children during COVID-19 pandemic: A community-based study from Punjab. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health 2022; 18(2): 112-25

21. Kaimal G, Ray K, Muniz J. Reduction of cortisol levels and participants' responses following art making. Art Psychother 2016; 49: 13-22

22. Reiss F, Meyrose AK, Otto C, Lampert T, Klasen F, Ravens-Sieberer U. Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents. PLoS One 2019; 14(3): e021370 23. World Health Organisation. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Geneva: WHO; 2020

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.