Cervical cancer is a major health concern, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Previous studies have emphasised the role of education and outreach in improving screening rates (Valdez et al, 2018; Liu et al, 2017). This study aimed to evaluate women's knowledge, awareness, and screening practices related to cervical cancer in outpatient settings. Cervical cancer remains a leading cause of mortality among women worldwide, particularly in developing countries (Andreassen et al, 2018). Screening programmes such as Pap smears and HPV testing have demonstrated efficacy in early detection and prevention (Abugu & Nwagu, 2021; Deguara et al, 2020). However, lack of awareness and infrastructure continues to impede efforts in regions like India (Teigne et al, 2022). This study aims to assess women's knowledge of cervical cancer screening in Maharashtra and analyse the influence of socio-demographic variables

Background of the Study

Cervical cancer accounts for approximately 6-29 percent of all cancers in Indian women, with significant disparities between states. Despite the availability of effective screening tools, barriers such as financial constraints, cultural beliefs, and inadequate health education hinder widespread implementation (Enyan et al, 2022). Previous studies indicate that education, occupation, and access to information significantly influence women's knowledge and participation women's knowledge and participation in screening programmes (Kamanga et al, 2023).

Need of the study:

India’s cervical cancer mortality rate underscores the urgent need for widespread awareness and effective screening programmes. Rural and low-income populations are disproportionately affected due to limited access to healthcare and preventive measures (Momenimovahed et al, 2021). This study seeks to bridge the knowledge gap and provide evidencebased recommendations to improve cervical cancer screening uptake in resource-limited settings.

The study focuses on disseminating knowledge about cervical cancer screening among women aged 30-59 years attending the gynaecology OPD of a tertiary care hospital. The findings aim to guide future educational interventions and policy initiatives to enhance screening rates.

Objectives

The study was undertaken (1) to assess the knowledge regarding cervical cancer screening among women attending the gynaecology OPD; and (2) to analyse the association between knowledge levels and selected socio-demographic variables.

Review of Literature

Sharma et al (2021) conducted a communitybased study in Northern India and highlighted that only 19 percent of women were aware of cervical cancer screening, pointing to persistent low awareness, especially in rural settings. Basu et al (2020) corroborated similar findings across India, reporting only 23 percent awareness and underlining the need for strengthening the national screening programmes. Mutyaba et al (2017) explored cervical cancer screening in Uganda, revealing that education level and health system barriers significantly impacted screening uptake among women in low-income settings.

Singh Badaya (2018) reviewed factors affecting cervical cancer screening in India and found that education, income, and occupation strongly influenced women’s participation in screening programmes. Gakidou et al (2019) reported global disparities in screening coverage, with many lowand middle-income countries showing low uptake due to socio-economic inequalities. Bhatla et al (2020) demonstrated that visual inspection methods combined with community education significantly improved screening uptake and awareness among women in community settings in India.

Methodology

Research design: This quantitative, cross-sectional study employed structured questionnaires to collect data from 53 women aged 30-59 years attending the gynaecology OPD. A probability-based simple random sampling technique was used.

Variables: Demographic variables were: age, marital status, education, income, and number of deliveries; discrete variables - history of screening; continuous variables - age and income.

Sample size: For this study, the sample size was arbitrarily decided to be 50 women who came for a visit to the gynaecology OPD.

Sampling technique: A simple random sampling technique was adopted to recruit samples from the accessible population who met the inclusion criteria.

Selection of tool: The standardised structured tool was selected, which includes sociodemographic data and a knowledge questionnaire on post-partum intrauterine contraceptive device. It was composed of background data, and knowledge scale.

The background tool consisted of 9 items, which dealt with the information like age, education, income, any family history of cervical screening, prior knowledge about cervical cancer screening, source of information, whether attended any cervical screening camp or not. Knowledge scale had 15 multiple-choice questions regarding the cervix, cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening. The rating scale has been classified as:

0-5: Poor

6-10: Good

11-15: Very good

As measured on knowledge scale, the maximum measured was 15.

Validity of tool: The construct, face, and content validity of the tool were established by experts in the field of nursing, obstetrics & oncology specialities. The suggestions given by the experts were incorporated into the study, and the tool was finalised.

The reliability of the knowledge score scale was established.

Data collection: Data were collected over 10 days using validated questionnaires, including sociodemographic details and a knowledge scale. Knowledge scores ranged from 0-15, categorised as poor (0-5), good (6-10), and very good (11-15).

Ethical considerations: Approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. Informed consent was secured from all participants.

Results

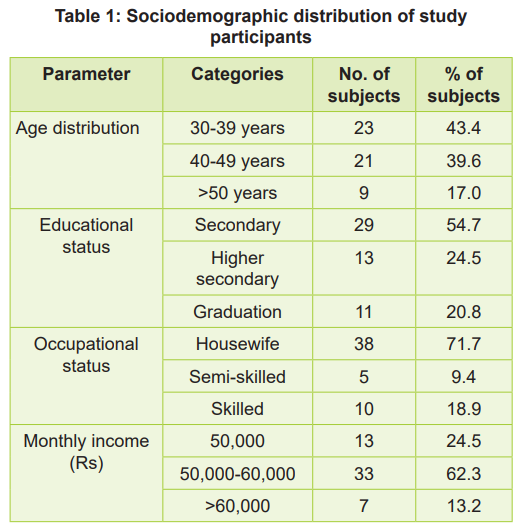

The socio-demographic profile of the participants showed that most were housewives (71.7%), had completed secondary education (54.7%), and were in the age group of 30-39 years (43.4%) (Table 1). Awareness of cervical cancer screening was low, with only 22.6 percent of respondents having heard of screening, and posters or health education programmes were cited as the main sources of information. Although the level of knowledge varied significantly across age groups, younger participants (30-39 years) showed slightly better knowledge than older age groups.

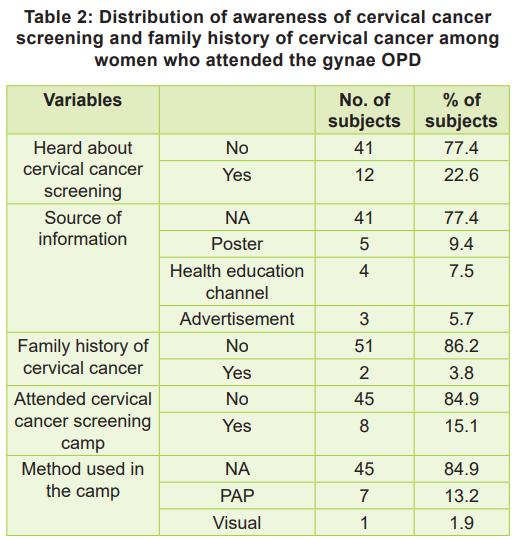

Table 2 depicts that the majority of women (77.4%) had no awareness of cervical cancer screening, and among those aware, the main sources of information were posters (9.4%), followed by health education channels (7.5%) and advertisements (5.7%). Only 3.8 percent reported a family history of cervical cancer. A significant proportion (84.9%) had never attended a cervical cancer screening camp, and among those who did, the PAP smear (13.2%) was the most commonly used method, while visual inspection was rarely used (1.9%).

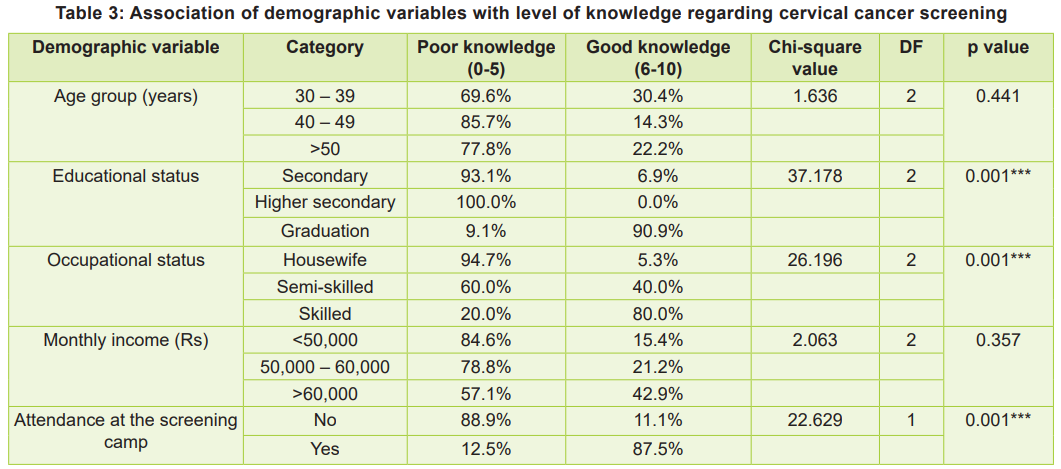

Table 3 depicts that educational status played a pivotal role, and graduates demonstrated the highest levels of awareness compared to those with only secondary or higher secondary education. It further revealed that monthly income influenced knowledge, as seen with participants in higher income brackets demonstrating better understanding of cervical cancer screening and also elaborated that the age group 40-49 have significantly better awareness compared to the age group 30-39 and >50 years.

Overall, knowledge assessment revealed that 77.4 percent of participants scored in the lowest category, indicating poor understanding of cervical cancer and its screening. When stratified by education, 90.9 percent of graduates had good knowledge compared to only 6.9 percent of those with secondary education (Table 3; p<0.001). Similarly, occupational differences were observed, with 80 percent of skilled workers demonstrating good knowledge compared to only 5.3 percent of housewives (Table 3; p < 0.001). Despite low awareness, the overall participation in cervical cancer screening camps was only 15.1 percent (Table 2). A notable finding was that knowledge positively influenced participation; 87.5 percent of those who attended screening camps scored higher on knowledge assessments (p < 0.001). Barriers to participation were primarily related to lack of awareness, affordability, and accessibility issues. The association between attendance at cervical cancer screening camps and knowledge levels was also highlighted. Participants who attended camps showed markedly better awareness, with 87.5 percent achieving good knowledge scores compared to only 11.1 percent among nonattendees.

This comprehensive analysis highlights significant gaps in knowledge and participation, underscoring the importance of policy-level interventions to enhance awareness and increase screening rates.

Discussion

Our study highlights gaps in awareness regarding cervical cancer screening, especially among lesseducated and unemployed women. Educational interventions and policy changes are crucial to overcoming barriers and improving screening uptake. Comparisons with similar studies indicate consistent trends across low- and middle-income countries (Sharma et al, 2021). For instance, the role of culture and religion in influencing cervical cancer screening has been reported extensively (Momenimovahed Z et al, 2021).

The present study revealed significant gaps in knowledge and awareness regarding cervical cancer screening among women attending the gynaecological outpatient department. A majority (77.4%) of participants demonstrated poor knowledge, while only 22.6 percent had heard of cervical cancer screening, aligning with previous studies in similar settings. Based on a study in North India, Sharma et al (2021) reported that only 19 percent of women were aware of cervical cancer screening, highlighting persistently low awareness in Indian populations, especially among rural and semi-urban women. Similarly, Basu et al (2020) reported low screening awareness (23%) in their multicenter study across India, which corroborates the present findings.

Educational status emerged as a critical determinant of knowledge. In the current study, 90.9 percent of graduates had good knowledge, compared to only 6.9 percent among those with secondary education, which was statistically significant (p<0.001). This is consistent with the findings of Mutyaba et al (2017) who reported that women with higher educational attainment had significantly better knowledge and a higher likelihood of participating in screening programmes.

Occupational status was another significant factor with skilled workers (80%) demonstrating better knowledge compared to housewives (5.3%), supporting the findings of Singh & Badaya (2018) where working women showed greater awareness and more proactive health-seeking behaviour compared to homemakers.

Income level also influenced knowledge, as women in the higher income bracket (> Rs 60,000) had 42.9 percent good knowledge, reflecting the socio-economic disparities in health literacy, which is in line with Gakidou et al (2019), who emphasised that socio-economic inequities continue to impact preventive health service utilisation, including cancer screening.

Importantly, attendance at cervical cancer screening camps was only 15.1 percent, yet 87.5 percent of those who attended demonstrated good knowledge. This strongly suggests that direct exposure to screening services significantly improves knowledge, as also evidenced by Bhatla et al (2020), who observed that participation in screening camps was associated with improved awareness, dispelling myths, and encouraging further participation.

The findings also reflect cultural and accessibility barriers. The main barriers reported included lack of awareness, affordability, and accessibility, which have been similarly highlighted by Denny et al (2015) in their global review, emphasising that knowledge gaps, cultural stigma, and health system barriers are key factors limiting cervical cancer screening uptake in low-resource settings.

Nursing Implications

Promoting awareness and education: Nurses have an essential role in educating women about cervical cancer, its risk factors, and the benefits of early screening. They can use outpatient departments, community visits, and health education sessions to share accurate information.

Community engagement and outreach: Nurses can lead and support community-based screening programmes, especially targeting women who have low awareness or limited access to healthcare. They can collaborate with local health workers to reach more women at the grassroots level.

Support for screening programmes: Nurses should actively participate in organising cervical cancer screening camps and ensure that women are guided properly throughout the process, including follow-up care when needed.

Addressing barriers through counselling: Since cultural beliefs and misconceptions were identified as barriers, nurses can provide individualised counselling that is culturally appropriate, helping women feel comfortable participating in screening services.

Advocacy role: Nurses can advocate for making cervical cancer screening a routine part of women’s healthcare services, ensuring better accessibility and affordability for all women, particularly those from low-income backgrounds.

Recommendations

Strengthen educational efforts: Organise regular educational programs focusing on cervical cancer awareness and screening, using simple language and locally understandable methods, like posters, talks, and group discussions with special attention to women with lower education levels, housewives, and women from low-income families.

Enhance access to screening services: Ensure that screening services are made available and accessible in both hospital and community settings, particularly in areas with low screening rates.

Train healthcare workers: Provide ongoing training to nurses and other healthcare providers on cervical cancer prevention, screening methods, and effective communication strategies.

Policy-level actions: Advocate for government and health authorities to implement policies that support free or low-cost cervical cancer screening services, along with awareness campaigns in both urban and rural settings.

Limitations: The study was restricted to OPD attendees; findings may not generalise to community settings. There may be potential response bias due to self-reported data.

Conclusion

Most women demonstrated poor knowledge about cervical cancer screening. Enhanced educational campaigns and healthcare initiatives are essential to improve awareness about screening and participation in screening programmes.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.